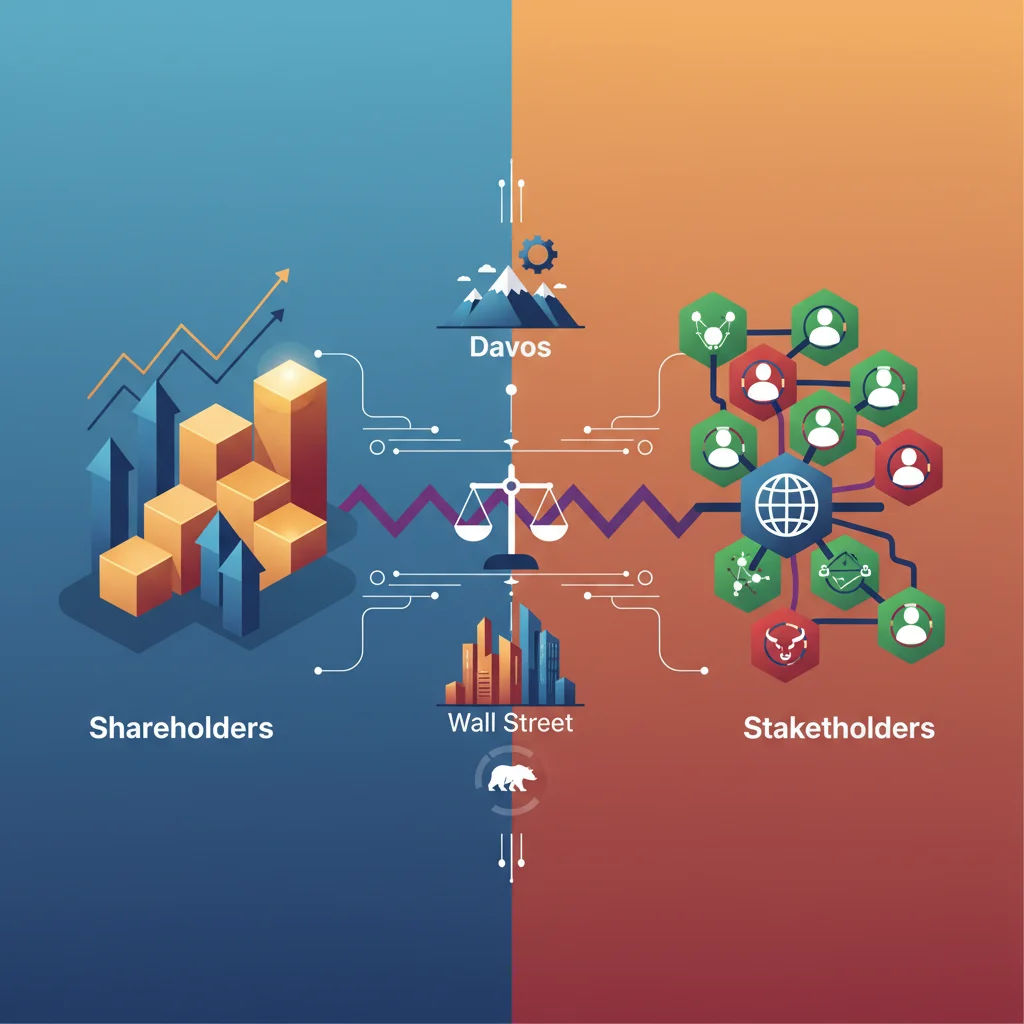

Shareholder vs. Stakeholder: Decoding the Economic Debate That Dominates Davos and Wall Street

In the rarefied air of Davos, where global leaders converge to map out the future of the world economy, a single speech can reignite a debate that cuts to the very core of modern capitalism. When Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau addressed the forum, his message, echoing a growing global sentiment, prompted a sharp response. In a letter to the Financial Times, Patrick J. Allen articulated this “push back,” highlighting a fundamental tension that defines today’s financial landscape: the battle between shareholder primacy and stakeholder capitalism.

This isn’t just an academic squabble. It’s a conflict that dictates corporate strategy, shapes investment portfolios, and influences the trajectory of the global economy. For investors, finance professionals, and business leaders, understanding the nuances of this debate is no longer optional—it’s essential for navigating the complexities of the modern stock market and the evolving principles of value creation. What is the true purpose of a corporation? Is it solely to maximize profit for its owners, or does it bear a broader responsibility to its employees, customers, community, and the environment? Let’s dissect this foundational question and explore its profound implications for finance and investing.

The Friedman Doctrine: The Gospel of Shareholder Primacy

To understand the current “push back,” we must first travel back to 1970. The world was in a state of flux, and the role of corporations in society was a topic of heated discussion. It was in this environment that Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman published a seminal essay in The New York Times Magazine titled, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” This piece would become the bedrock of corporate philosophy for the next half-century.

Friedman’s argument was both elegant and provocative. He contended that a corporate executive is an employee of the business’s owners—the shareholders. Therefore, their primary responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with the owners’ desires, which he argued “will generally be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society.” For Friedman, executives who pursued social agendas like reducing pollution beyond legal requirements or hiring the long-term unemployed at the expense of profits were, in effect, spending someone else’s money—the shareholders’—without their consent. He saw this as a form of “unadulterated socialism” and a fundamental breach of the agent-principal relationship.

This doctrine provided a clear, unambiguous mission for corporations: maximize shareholder value. This clarity fueled decades of economic growth, streamlined corporate governance, and created a simple metric for success: the stock price. The stock market thrived on this principle, as it allowed investors to evaluate companies based on a universally understood goal. For traders and fund managers, it made the complex business of capital allocation refreshingly simple.

Political Tremors: How a Tory Defection Signals Deeper Economic Risks for UK Investors

The Rise of Stakeholder Capitalism: A Broader Definition of Success

While the Friedman doctrine reigned supreme for decades, a counter-narrative was always simmering beneath the surface. This alternative view, now known as stakeholder capitalism, posits that a corporation’s long-term success is inextricably linked to the well-being of all its stakeholders—not just its shareholders. This group includes:

- Employees: Who require fair wages, safe working conditions, and opportunities for growth.

- Customers: Who demand ethical products, fair pricing, and excellent service.

- Suppliers: Who must be treated as valued partners.

- Communities: Where the company operates, and which are impacted by its environmental and social footprint.

- Shareholders: Who still expect a healthy financial return.

The argument is that by neglecting any of these groups, a company jeopardizes its long-term viability. A business that underpays its employees will suffer from low morale and high turnover. One that deceives its customers will lose its brand reputation. A company that pollutes its local environment will face regulatory fines and public backlash. In this view, maximizing shareholder value is not the primary goal, but rather the result of successfully serving all stakeholders.

This movement reached a watershed moment in August 2019, when the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs from America’s leading companies, issued a new “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation.” Signed by 181 CEOs, it officially moved away from shareholder primacy, committing instead to delivering value to all stakeholders. This was a seismic shift in the world of corporate economics, signaling that the debate had moved from the classroom to the boardroom.

To clarify the core differences, consider the following breakdown of these two competing economic philosophies:

| Aspect | Shareholder Capitalism (Friedman Doctrine) | Stakeholder Capitalism |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Maximize shareholder wealth (profits, stock price). | Create long-term value for all stakeholders. |

| Decision-Making Focus | Financial returns, quarterly earnings, market valuation. | Financial, social, and environmental impact. |

| Key Metric of Success | Total Shareholder Return (TSR), Earnings Per Share (EPS). | A “balanced scorecard” including customer satisfaction, employee retention, community impact, and financial profit. |

| Time Horizon | Often short-term, driven by quarterly reporting cycles. | Inherently long-term, focused on sustainable growth. |

| View of Social Responsibility | The responsibility of individuals and governments, not corporations. The business’s social duty is to be profitable. | An integral part of corporate strategy and risk management. |

Implications for Modern Finance, Trading, and Investing

This high-level debate has very real-world consequences for everyone involved in the financial ecosystem, from retail traders to institutional investors and corporate executives.

The Investor’s Dilemma: ESG and Value Alignment

The most direct consequence of the rise of stakeholder theory is the explosion of ESG investing. Investors are increasingly using environmental, social, and governance criteria to screen potential investments. They are betting that companies with strong ESG performance are better managed, less risky, and better positioned for long-term growth. Research from institutions like the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business has shown a consistent positive correlation between ESG performance and financial performance.

For finance professionals, this means that fundamental analysis must now extend beyond the balance sheet. It requires evaluating a company’s labor practices, its carbon footprint, and the independence of its board. For the average person investing for retirement, it means they now have the tools and the impetus to align their portfolio with their personal values.

Decoding the Market: Financial Lessons Hidden in the FT Crossword

The CEO’s Balancing Act

For business leaders, the landscape has become infinitely more complex. The clear, singular goal of maximizing stock price has been replaced by a multi-faceted mandate to appease a wide range of stakeholders with often competing interests. A decision to raise wages (good for employees) might reduce short-term profits (bad for shareholders). Investing in greener manufacturing (good for the community) could increase costs (potentially bad for customers and shareholders). Navigating this requires a sophisticated approach to strategy, communication, and a genuine commitment to long-term value creation that transcends quarterly earnings calls.

The Evolving Stock Market

The stock market itself is adapting. We are seeing the rise of ESG-focused ETFs and mutual funds, and ratings agencies now provide detailed ESG scores alongside traditional credit ratings. However, the “push back” mentioned in the FT letter is a reminder that many powerful market participants remain skeptical. They argue that stakeholder capitalism is a vague concept that can be used to excuse poor financial performance and reduce accountability. They believe that a focus on anything other than profit ultimately harms the economy by misallocating capital and slowing innovation.

The Future of Capitalism: A Synthesis Forged by Technology

The debate is far from settled. However, the path forward is likely not a complete victory for either side, but a synthesis. The future of corporate success will be defined by an ability to prove that serving stakeholders is the most effective way to reward shareholders. This is where financial technology will play a transformative role.

- Fintech and Data Analytics: Advanced algorithms and AI are making it possible to quantify the impact of stakeholder-centric initiatives. Companies can now measure the ROI of improved employee wellness programs or the brand value generated by a commitment to sustainability. This moves the conversation from vague platitudes to hard data, satisfying the demand for accountability from the shareholder camp.

- Blockchain and Transparency: Blockchain technology offers an immutable ledger to track supply chains, verify ethical sourcing, and ensure corporate promises are kept. This radical transparency can build trust with customers, regulators, and investors, directly addressing key stakeholder concerns.

- Democratization of Investing: Modern trading platforms have empowered a new generation of retail investors who are more likely to demand social and environmental responsibility from the companies they own. This creates grassroots pressure on boards and management to adopt a more balanced approach.

Ultimately, the conversation sparked by leaders at Davos and echoed by observers like Patrick J. Allen is a reflection of a changing world. The old model, which generated immense wealth but also contributed to externalities like environmental degradation and social inequality, is being challenged. The new model, while noble in its aims, is still struggling to define itself with the clarity and rigor that financial markets demand.

The challenge for the next generation of business leaders and investors is to bridge this gap—to build companies and portfolios that are unapologetically profitable because they are fundamentally purposeful. The future of the economy doesn’t belong to the shareholder or the stakeholder alone; it belongs to those who understand that their fortunes are, and always have been, deeply intertwined.